|

PERSPECTIVE ARCHIVE |

|

|

Art and Physics

by Tom Rogers

1/11/09

|

|

|

Several weeks ago I had the pleasure of making a presentation at Worfford College and talking to physics teacher Steve Zides about his efforts to merge science and art, particularly in his course on the Physics in plays. According to Steve, teaching a more conventional course for non-physics majors didn't work well because he would get every type of student from those who had previously gotten 5s in high school on the calculus based AP Physics exam to those who barely passed high school algebra. He found that combining physics with the arts leveled the playing field and made it possible for a wide diversity of students to benefit from his class. At first glance, physics and the arts look like they're at opposite ends of the spectrum. The arts are often viewed as creative activities, flowing from the imagination, free of any constraints. But, anyone who has ever watched an episode of American Idol tryouts, knows there are thousands of people who imagine they have the stuff to be performing artists--singers--and are extremely creative in their performances but still don't achieve anything that could be labeled artistic. The truth is that art is highly constrained by many principles such as the need to sing on key and favorably impress one's audience. As for physics being the opposite of art, consider that all of the principles in physics were discovered because someone with a highly creative mind first imagined them. Subsequently, engineers have used these principles to create the millions innovations of modern life, similar to the way musicians have used the principles of cords, harmony, and rhythm for composing music. Still, the relationship of physics to the arts is not just based on similarities. Physics is--like it or not--actually a tool of the arts similar to the way it is a tool of engineering. Since it is the science of motion, light, sound, and all electronic forms of communication, virtually all forms of art involve physics. Knowing something about physics is going to be helpful to anyone pursuing the arts. It's good to see a wider group become involved with physics because in the long run, this type of involvement and mixing of ideas is going to lead to a better understanding of both the arts and physics. |

|

|

We're Now a

Book.

12/24/07

|

|

|

If you've wondered why we've

been posting less content lately, the

truth can now be told: we've been working on a book. The ISMP web site has always been a labor of love by a few

unpaid, part time workers and so a major project like

writing a book consumed most of our resources.

The whole process took about

three years and a lot of effort, not to mention about 7

years of effort on our web site before we even began the

book.

From years of web

site reader input we knew our audience wanted some

calculations in the book but also wanted to just plain have

fun.As result,

the book has the same

irreverently humorous tone as the web page and is as much

about having fun as teaching physics. The mathematics in it

uses no calculus and the physics is pretty much limited to

concepts taught in high school. For fast reading, the

calculations are set up in boxes and can be skipped.

Having some calculations makes

the book more useful for students who've accepted the

challenge of learning physics. Surprisingly, based on our

web site's reader response, a lot of them have been out of

school for some time and are now trying to compensate for

what they didn't learn or didn't have the opportunity to

learn in the classroom.

The book is also intended to give aspiring filmmakers, science fiction writers, and just plain moviegoers a helpful perspective. We continue to think that art, physics, and mathematics are all part of the same creative human experience. What's more, we continue to think that all can be entertaining and enlightening.

|

|

|

Whores of Science? by Tom Rogers 12-27-06 |

|

|

After reviewing the fruits of their labors, the late S. I. Hayakawa, famous for his work in semantics, once described motivational researchers as “…those harlot social scientists who, in impressive psychoanalytic and/or sociologic jargon, tell their clients what their clients want to hear…” Their fruits included oversized, overpowered, 50s era cars designed to look like rocket ships complete with those marvelous innovations: tail fins—all to compensate for neurotic male fears of impotence. We can only wonder what Hayakawa might have said if he’d looked at fruits of scientists who consult for movies. Even the Core—the epitome of bad movie physics—had no less than 3 PhD level science consultants. Here’s a film with scenes such as the Golden Gate bridge collapsing when overheated by microwave radiation from the Sun coming through a hole in the Earth’s magnetic field—never mind that the Earth’s magnetic field is incapable of blocking microwave radiation and that the Golden Gate bridge has been getting the available microwaves from the Sun for decades without collapsing. Hollywood knows that authentic sounding jargon can create the illusion of reality even when none exists. Certainly that’s worth the price of a PhD consultant, although, one isn’t actually required. The task could be done by a part time researcher with a high school physical science education and the ability to google. The real reason for the PhDs: listing a few in the credits provides enough respectability to snuff most sparks of doubt before they can ignite into full blown skepticism. A typical innocent-minded moviegoer can’t fathom the possibility that a highly trained, analytically minded, scientist would ever put his or her name on a less than scientific product. So why would otherwise respectable scientists surrender their virtue to dispensers of drivel and for what—mere money or a few fleeting moments of fame? There are at least three possibilities:

Expecting abstinence from would-be movie science consultants would be about as effective as proposing population control by universal celibacy. With billions of people, someone will always be pregnant. On the other hand, science consultants should, at least, keep their standards high and pay attention to their client’s intentions before entering into contracts. Merely demanding some scientific accuracy along with their paychecks would help. With their virtue at stake, even thinking “wowww mannnn” should sound alarms. Lowering the public’s expectations would also help. While we often get less from experts than we pay for, we rarely get more. When we feel miserable with conditions like asthma, allergies, arthritis, or the common cold and seek a remedy, we can end up paying $80 for a few minutes of “doctor’s orders” and are lucky to get some relief, never mind a cure. By contrast we pay $8 for two hours of movie entertainment with only a fraction going to the science consultants. Why should we expect anything from them? Expecting nothing would actually help. Take away the bogus reasons for hiring science consultants and moviemakers might actually demand some science for their money. Expecting moviemakers to be faithful to their science consultants may be too much to ask. Indeed, good science isn’t always required for good movies. There is a place for fantasy and parody. But, if science consultants were considered more than just marketing objects, we just might be able to get some movie physics without the fins.

|

|

|

Bioinformatics and Hollywood by Tom Rogers 7-29-06 |

|

|

I’ve recently returned from a weeklong course in bioinformatics (using computers for analyzing genetic data). Having gotten a degree in engineering and worked as one for a long time before becoming a high school physics and computer science teacher, I’ve generally not taken the time for such interesting diversions. While I’ll probably not do much in the field, I’d have to say it’s certainly enticing. The field is incredibly dynamic. In 1998 the total sequencing output of the Human Genome project was 200 Mb. By 2003 the DOE Joint Genome Institute alone sequenced 1,500 Mb in merely the month of January! 1 . Within 10 years we’ll be able to hand parents a genetic profile of their offspring complete with predicted diseases. Once impossible tasks are now becoming not only possible but fully automated. For example, the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, and 454 Life Sciences Corporation, in Branford, Connecticut, announced recently that they hope to complete a first draft of the entire 3 billion base Neanderthal genome within the next two years 2 –using 38,000 year-old fossils. New DNA sequencing data is being amassed faster than our ability to analyze it. Much is freely available on the internet. And, computer nerds get this: a DNA sequence is nothing more than a lengthy string with four characters, A, C, G, and T! In other words, a high school student would be able to write programs to analyze DNA sequences by the end of his or her first semester of AP Computer Science if not before. Considering that data is being generated faster than the professionals can analyze it, even a bright high school student could make a discovery. It’s almost the wild west or at least reminiscent of the earlier days of desk top computing. Where the new frontier of genetics differs from the old west of computing is in the degree of government regulation and number of serious moral issues—things like accidentally unleashing plagues and/or creating new human genetic defects. Needless to say, garage startups in genetic engineering are not likely to happen. Still, bright high school students making discoveries using PCs is not only doable but pretty cool. You people know who you are and I hope we’ll be hearing a lot about you! For the same reasons, I hope we’ll also be hearing more about corporate folks setting up awards and support for the young people with ideas. The educational infrastructure already available for learning about DNA is amazing. The South Carolina DNA Learning Center located at Clemson University (where I attended the bioinformatics course) offers all kind of training including hands-on Saturday courses open to the public. It’s the offspring of the Dolan DNA Learning Center, the world's first science center devoted entirely to public genetics education with a web page featuring everything from video clips to Geneboy, a tool for exploring bioinformatics. One of the biggest things that struck me during my week of training was the considerable potential for book and movie material. We were told about a plant geneticist who spent time wandering all over South and Central America testing coca plants (the ones used for cocaine production) to see if they had been genetically modified for resistance to herbicides. Apparently, the US government regularly sprays coca crops with herbicides and had been noticing that the plants are becoming resistant. Not only was the coca-testing geneticist in constant danger of being bumped off by drug dealers, but he had to smuggle cocaine leaves back to his lab for a more detailed analysis. While the tests proved negative, the theory behind them was all too real. We were told that a bright criminal with some biology background could fairly easily come up with a way to create a herbicide resistant coca variety. Imagine the black market value of that capability. It sounds like something in a movie. At the course, we created genetically modified bacteria by taking a jelly fish gene that makes it phosphorescent in UV light and inserting it into the bacteria. A few drops of this and that, a little heating and cooling, some time to grow the culture, and viola, glow-in-the-dark bacteria. The process was eerily simple. Whenever I’m around life science people, I like to ask two questions: 1) is humanity about to take control of its own evolution? 2) Will it be possible to significantly extend, say double human lifespan? So far, I haven’t gotten an answer. However, I think from a moral, ethical, and societal perspective these are two of the most profound questions facing humanity and before my life is done, I expect the answers to be yes. It seems to me that these would be very profound questions for moviemakers to explore. Hollywood has given us some genetic engineering based offerings from the relatively intelligent GATTACA to the inane and thermodynamically impossible The 6th Day. The movie The Island , about people cloned for body parts, falls somewhere in the middle—an intelligent work that degenerated into a mindless action piece for box office purposes. Considering the uniqueness of the time we live in and not just the scientific but moral issues ahead, we could certainly use some intelligent works of fiction and movies to help with the discussion and understanding. Hopefully Hollywood will find ways to balance societal needs for understanding with filmmaker needs for box office success. I hope we’ll be hearing more about intelligent-movie maker successes as well as bright high-schooler discoveries. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Hollywood Computer Gene by Tom Rogers 5-31-06 |

|

|

It was the end of the school-day, but students were exiting the back door a little too fast, so I headed in the same direction. Two of the coaches (football and wrestling) evidently noticed the same migration and headed out the door even before I arrived. By the time I got there the young men about to boil over into a fight had instead melted into the crowd, which was now dispersing. As I turned to go back, one of the coaches asked why I had come out. I mumbled something about wanting to see if I could help. They roared with laughter. It was pretty funny: the faculty nerd helping the faculty macho-guys break up a fight. But coaches are also sensitive guys—in their own way. One quickly changed the subject and told me he had to take a course in order to maintain his teaching certification and that he didn’t want to waste the time and money. Could I hack into the school district’s computer system and change the records for him? I took the request as an effort to re-inflate my punctured ego. I lied, saying that I could easily hack the computer system but that it would be cheaper to take the course than pay my fee. The truth is I could have bench pressed the coach way easier than hack into and change his records. As the faculty nerd it’s assumed that I have a gene enabling me to magically solve computer problems. Like all myths, this one has at least some factual basis. For example: the time I fixed a teacher’s monitor. I pushed the on-button a little more firmly than she and the monitor came to life. In mere seconds, I had fixed what she’d obsessed over for hours. I’ve learned to shrug and say, ”gosh I don’t know,” when asked how I fixed a problem.” People seem terribly disappointed if I explain. I attribute most of this mythical computer gene to movies. Pencil-necked geeks nourished by fast foods have become ubiquitous film characters. They can take over nuclear power plants in seconds via the internet—all for the reward of a Twinkie. Real computer wizards are far different. I know because, occasionally, I teach one. Take Jerry, for instance (I’ve changed his name). We were sitting around the high school’s computer lab a few years ago pondering a stack of donated obsolete computers that were collecting dust in the corner. Someone (now an aspiring science fiction writer) said, “Why don’t we build a Beowulf system.” I said, “Sounds good. What’s a Beowulf system?” It turned out it was, at the time, the hottest new form of super computer and could be assembled by linking together multiple computers loaded with Linux operating systems. Jerry was already ga-ga over Linux, so I told him to do it for a science fair project. We had 30 of the latest and greatest Pentium IIs in the lab, enough, in those days, to make a world-class Beowulf system, but the district computer guys were highly unenthused about duel booting them with Linux. They were sure we’d somehow hack into the network’s servers and mess up the data bases. They said so emphatically in memos to my principal. For the moment we were stymied. I decided to set up a 3-computer-system at my house for development purposes. Jerry came over one weekend and worked with one of my sons for over 30 hours straight, struggling to get the 3-computer Beowulf system working. When I drove him home—he had flunked his driving test twice and had no license—I asked him if he hade made any progress. He smile brightly and said no but that it was so much fun trying. After a few more months of effort he finally did learn how to set up a Beowulf system but the district guys were still unmovable. Then it came to me in a rare flash of genius, if we didn’t tell anyone and installed the system anyway what was the worse case scenario? I could be fired, but then I could get a higher paying job, write a tell-all book, and sell the movie rights—perfect. We concealed cat 5 cables on our persons and quietly walked into the school library’s server room. The server room held the computer lab’s network switch and once inside we could make the necessary connections for creating the Beowulf system. I didn’t tell the librarian or principal about what I was doing—I didn’t want competition when looking for a new job. With the network connections completed, I spent 9 hours loading Linux on 25 of the computer lab’s machines. The next day was Saturday and I made arrangements to bring in Jerry and a small crew of student volunteers to finish the installation, along with a supply of pizza and soft drinks. Jerry got all the Beowulf software installed along with some parallel programs he had written and we fired up the system. It worked flawlessly and for a day we had the fastest computer system in South Carolina. During our adventure, it started snowing and so I drove Jerry home after dark through snow covered streets. Most of our crew left early as soon as the snow started falling. Jerry was featured in local TV, radio, and news paper pieces as the kid who built a super computer. We printed t-shirts (they’re still available in the Intuitor Store) and made an appearance at the local Barnes and Noble. Jerry went on to the International Science Fair, then Carnegie Mellon University with a full ride scholarship and graduated four years later with a master’s degree in computer engineering. The last time I saw him he still had no driver’s license. As for me, I finally gave in to the district guys and removed the Beowulf system. They made it clear that I could have a Beowulf system in the lab or an internet connection but not both. I didn’t get fired, didn’t get a higher paying job, and didn’t write a tell-all book. I’m still teaching. Yes, Jerry triumphed, but it was done with a good bit of tedious work over a time span of months—although to Jerry it was all jolly fun. Had the movie version been made Jerry would have definitely been depicted as possessing the mythical computer gene. The movie would have probably fictionalized the event by showing us using the Beowulf to hack into the district computer, alter the coach’s records, play tricks on the computer guys, and give me a raise, all during the deadliest blizzard to ever strike America. True the fictionalized version would have contained some grains of truth and been more exciting, but I prefer the real one. It was exciting enough. |

|

|

Physics and Giant Green Grasshoppers by Tom Rogers 5-14-06 |

|

|

It’s May, the month for Mothers Day, and although it has little to do with movie physics, it’s hard not to think of her. I’d characterize my mother as a people nerd. She could read people like an equation and calculate solutions to them faster than a normal person can add two single digit integers. On the other hand, she had no particular need for their approval and couldn’t have cared less about her public image. When I have a people problem I don’t think what would Jesus do or God say, I think, “how would mom handle it?” While her solutions were not necessarily Biblical, they were eminently effective and even in the darkest of circumstances usually made people feel better. That was precisely what she did when selling cosmetics in a department store during the Great War—she made people feel better, far more effectively than anything sold in a bottle. She set a store record for ringing up $1100 worth of sales on a single day during the Christmas season. Other salesgirls routinely sent difficult or impossible-to-please customers to mom and she’d sell them a bag full of the latest (and usually most expensive) products. What’s more they’d return as her regulars. It’s not that she knew all that much about cosmetics, she knew people. When the son of a neighbor went to prison she wrote him weekly for five years until he was released. When one of her former Brownie Scouts had hard times and no money to buy Christmas presents for her young children mom sent a check. She was a constant comfort to a friend dying of cancer right up to the end and then a comfort to her friend’s grown children. After hearing about a young girl bed ridden with kidney disease, mom sent regular care packages with games and small toys inside to help her occupy her mind. I could go on. In her later years, Mom could sit quietly in an airport and total strangers would walk up and talk to her like they were old friends. When she went grocery shopping she’d invariably pick up a couple of her fellow shopper’s life stories along with her purchases. She was a people magnet and aside from rapists and child molesters (her attitude towards them too brutal to print), she loved just about everyone. She came to live with us during her final years and we were blessed to have her in our home. Always the physics teacher and dutiful son (well, at least physics teacher), I felt compelled to offer her the stress relieving physics background her education had failed to provide. It was a gift of myself. 5 + 7 = 13 was mom’s idea of higher math. She was passionate about math, passionate about hating it and, by association, anything with math in it, including physics. Yet, she’d dutifully balanced her check book—to me, a mind-numbing chore, so there had to be at least a glimmer of hope. Okay, I learned a long time ago that everyone was not cut out to be an engineer, that each person is special, and that each has his or her own unique contribution to make. I didn’t just respect mom’s uniqueness, I was mystified by it. Still, I just knew that her attitude toward physics had to be a result of a physics-starved education. In fact, I actually get a surprising number of e-mails from middle aged or older people who—having missed out in their earlier education—are now trying to learn physics to compensate. Some say they don’t understand the equations but are nevertheless fascinated by the principles. Given a gourmet taste of physics nourishment, surely mom would come around and be happy for doing so. “Let’s learn some physics,” I cheerily announced—all but saying it would crush my spirit if she responded with anything less than enthusiasm. Her face contorted, she stuck out her tongue, and made a sound that could best be described as retching. People skill aside, mom was never one to sugar coat her meaning and while I’m sure she clearly read my delicate emotional condition, she was unmoved. As a child I’d seen her crush a giant cockroach with her thumb while the rest of us stood back in fear. Mom never allowed anything to rule her and wasn’t about to start on my account. I waited a few days and tried a less direct approach. “Mom have you ever heard of inertia?” Out came the tongue. This from my own mother—the same one who cherished the giant green grasshopper I’d given her as a mother’s day gift when I was a small child. Nothing worked in spite of many efforts. Maybe if I’d had more time, maybe if I’d used movie physics, maybe if I’d been a better nerd, who knows? I’d have probably never given up. God knows, she never gave up on me. Even when I tried to teach her physics and she stuck out her tongue; I still knew she loved me and I her. |

|

|

Nerds are Easy by Tom Rogers 4-14-06 |

|

|

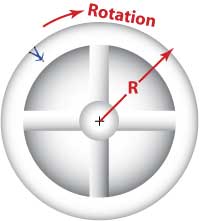

The artificial feeling of gravity is directly proportional to the distance from the center of rotation. If the spacecraft’s diameter were, say, 12 ft (3.7 m) an astronaut’s head would be located near the center at what would feel like zero gravity while his or her feet would feel like they were in Earth-like gravity. Sitting down or standing up would likely cause nausea. A rotating spacecraft would need to be 1000 ft (305 m) or more in diameter to comfortably simulate the feeling of gravity without nausea. In such a craft, the artificial feeling of gravity would vary by less than 2% between a person’s head and feet, hopefully, a tolerable amount for most individuals. At that, the craft would have to turn a complete revolution every 15.2 seconds, so it would be like living on a merry-go-round. While getting the craft rotating would take a lot of energy, once done, there would be essentially no air resistance or friction to slow it down. |

|

|

With the exception of the space station in the movie 2001, movies rarely get the details right about artificially simulating the feeling of gravity. At best, the spacecraft is too small. At worst it’s rotated in some ridiculous manner that bears no resemblance to the rotation needed. Filmmakers for movies like the Star Trek or Star Wars series don’t even try. They simply assume super advanced space-travelers would know how to create real gravity, so that conditions aboard their spacecraft would be indistinguishable from those of the studio where the movies are shot. The moment of truth finally came: the astronaut asked what I thought about Apollo 13. Here I was, talking to a highly qualified engineer with first hand knowledge of space travel, and we’d just agreed that space movies were nonsense. I hesitated, but what could I do? I muttered that not only was it one of my favorite movies but that it was clearly one of the best examples of good movie physics. He smiled broadly and concurred. I suspect he had experienced some of the same reservations about expressing his opinion before he knew mine, as I had about being forced to tell mine before I knew his. He’d beaten me to the draw by asking first. These NASA guys are definitely quick. For Apollo 13, the astronaut had expected the usual nonsense with people walking around in the space craft just like on Earth, but was genuinely amazed when he saw that the moviemakers had at times simulated outer space gravity conditions by filming scenes in a diving aircraft—NASA’s KC-135A, nicknamed the Vomit Comet. While flying on a parabolic trajectory, this aircraft provides about 25 seconds of apparent weightlessness but unfortunately has to eventually pull up from its dive, giving the sensation of about 1.8 times Earth’s gravity—a cycle that drives the inner ear bonkers, producing mild to extreme nausea. My astronaut acquaintance noted that the space flight scenes were obviously filmed in an aircraft judging by the vibration of various objects. Nonetheless, the vibrations were totally forgivable in light of what the moviemakers had done to create an overall sense of realism. The conversation illustrates an important point: When it comes to movie physics, nerds as well as astronauts are actually easy to please. Get just one unexpected detail right and we get all giddy, to the extent that we hardly notice the small stuff. Okay, maybe we don’t buy enough tickets to offset the added bother but then nerd pleasing attention to detail certainly didn’t hurt Apollo 13. The movie was third highest grossing film in 1995, not to mention, wining 2 academy awards and seven additional nominations. |

|

When Oprah Winfrey looks in the mirror she sees a reflection of the common mind of America, so it’s no surprise that when James Frey’s book, A Million Little Pieces, came out, she embraced it. The book is a tale of redemption from alcohol, crime, and drugs—what could be more inspiring. But then the truth began to leak. Parts of the book had been exaggerated or even outright fabricated. What was Oprah to do?

The book had been listed as nonfiction but clearly contained fictional elements. Unlike the movie-going public, the reading public lacks the phrase “it’s only a book”. Readers have expectations. Television’s talking heads began chewing Frey up and spitting him out.

When he appeared on Larry King Live, it looked like Frey was about to be fed to a world-class meat grinder—then an amazing thing happened: Oprah called. She had peered into her magical mirror and seen viewer comments about how Frey’s book had inspired them. So what if it had a few exaggerations and fabrications. To Oprah all the fuss was “much ado about nothing.”

To Frey the call could not have been better if it had come from God. He was vindicated—freed from the chains of mere facts. But wait, the mirror was about to turn ugly. It was about to jump off the wall and beat poor Oprah over the head with a deluge of angry e-mails. It seems that facts did matter after all.

The brave (?) Oprah summoned the dastardly Frey to the sacred halls of television for the verbal equivalent of a public flogging. All of a sudden Oprah found she’d been “duped”. What’s more she concluded that Frey had “… betrayed millions of readers.”

Okay, it’s hard not to feel some sympathy for Frey after he was first endorsed, then defended only to be tongue-lashed by Oprah, but, to be honest, it’s about time such a blunt-force message was sent. Details and facts are an important part of truth. It’s one thing to make an honest mistake or hold a questionable opinion but another to deliberately manipulate facts and details for the sake of image or marketability, especially when the product is labeled nonfiction.

Unfortunately, there’s no such thing as a nonfiction movie. The label documentary, all too often, refers to a propaganda piece filled with half truths, out-of-context sound bites, and anecdotal evidence. The words “inspired by” or “based on” a true story mean next to nothing when applied to movies.

The absolute classic has to be the critically acclaimed 1996 movie, Fargo. It’s a dark comedy about a series of murders whose opening tells us:

"This is a true story. The events depicted in this film took place in Minnesota in 1987. At the request of the survivors, the names have been changed. Out of respect for the dead, the rest has been told exactly as it occurred."

We loved the movie and thought, “Wouldn’t it be fun to get a photo of us standing by the giant statue of Paul Bunyan located in Brainerd Minnesota and featured in the film.” (Had we looked in the magic mirror we’d have seen a bunch of yahoos staring back.)

It was summer and we’d already decided to drive to Montana for vacation, so it was a simple matter to plot a route through Brainerd, even as a last minute thought. As we packed up and drove off, the statue of Paul loomed large in our minds. Yes, we longed to see the mountains of Montana, the beauty of Glacier National Park, and the wilds of Yellowstone, but the highlight of our trip was going to be a picture with Paul.

As we drove toward Brainerd we worried that we might not find the statue. No problem, we asked a local when we stopped near the town. He politely explained that the movie was a parody, that the statue didn’t exist, and that no one in Minnesota ever talked with the accent depicted in the film (to us he sounded identical). We were sure he was misinformed and kept an eye out for Paul when we reached Brainerd. Much to our disappointment, his movie likeness was no where to be found. In fact, later research revealed that the movie was a total fabrication (read the fine print at the end of the movie’s credits and you’ll see the usual disclaimer that the entire movie was fiction.) As for the statue, it was erected temporarily in Hensel North Dakota, filmed, and removed.

Of course, no one ever really believes anything they see in movies (except for those aberrant souls who imagine likenesses of Paul Bunyan) so maybe Oprah-like scorn is unjustified when movies pass off nonsense as fact. On the other hand, maybe a movie with a title like Pearl Harbor should avoid fictional elements when they conflict with the facts of history or the laws of physics. Just possibly a movie about a real-life gut-wrenching disaster aboard a Russian nuclear submarine (K-19 The Widowmaker) really doesn’t need a fictional encounter with the US Navy to make it dramatic.

How about Armageddon? Is it really a good idea to imply that a plan for saving the world from a major sized asteroid could be slapped together in a couple of weeks, or that the asteroid could be split in half with a single nuclear bomb? Maybe even total works of fiction should adhere to the laws of physics, at least if they’re attempting to create the illusion of reality or deal with major threats to humanity.

A lot of moviegoers actually do pay attention to detail and are distracted or even annoyed by insultingly stupid movie physics (ISMP). Sometimes moviegoers, even those who should know better, end up believing movie nonsense. Okay, Oprah is not going to start railing about ISMP. But maybe, just maybe, movies should be a little more like books.

ISMP Perspective Archive